“It has been said that the Battle of the Crater is the most spectacular event in our history.” So wrote a local historian about the best-known event in the entire 292-day Siege of Petersburg. The siege began with four days of strong Union attacks on the eastern defenses of Petersburg from June 15 to 18, 1864. Within a short time lines of trenches separated the two armies. The lines between the Confederate Elliott’s Salient near Blandford Church and the Union lines opposite that position were only 133 yards apart. Lieutenant Colonel Henry Pleasants, a mining engineer in the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, suggested that digging a tunnel under the Confederate defensive lines and exploding thousands of pounds of gunpowder could result in the desired breakthrough. The commander of the Army of the Potomac, Major General George G.

“It has been said that the Battle of the Crater is the most spectacular event in our history.” So wrote a local historian about the best-known event in the entire 292-day Siege of Petersburg. The siege began with four days of strong Union attacks on the eastern defenses of Petersburg from June 15 to 18, 1864. Within a short time lines of trenches separated the two armies. The lines between the Confederate Elliott’s Salient near Blandford Church and the Union lines opposite that position were only 133 yards apart. Lieutenant Colonel Henry Pleasants, a mining engineer in the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, suggested that digging a tunnel under the Confederate defensive lines and exploding thousands of pounds of gunpowder could result in the desired breakthrough. The commander of the Army of the Potomac, Major General George G.

Meade was skeptical, but allowed the proposal to proceed.

Lieutenant Colonel Pleasants primarily used soldiers from the 48th Pennsylvania Regiment, which included about 100 coal miners-turned-soldiers to dig the tunnel. The digging began on June 25, and Pleasants received almost no logistical support from his higher headquarters. Digging in their underwear and shirts, his soldiers made remarkable progress. By the end of June, Confederate Brigadier General Edward Porter Alexander, Lieutenant General James Longstreet’s chief of artillery, surmised that the Federals were tunneling toward Elliott’s Salient. By July 17, the tunnel was 510.8 feet long and 20 to 22 feet below the Confederate soldiers in Elliott’s Salient. The digging could barely be heard above. Four days later The Richmond Whig newspaper printed an article on a Union mine at Petersburg. At 6:00 pm on July 28, Pleasants reported that the tunnel was packed with 8,000 pounds of gunpowder and was ready for detonation.

Meanwhile, the Union planning for the attack after the mine exploded continued. The Union commander and Meade’s superior, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, planned to make the explosion part of a grander design, with demonstrations at Richmond, north of the James River. Major General Ambrose E. Burnside’s IX Corps would be the attacking force, and his objective would be Well’s Hill where Blandford Church stood. From this prominence in Petersburg, Union artillery could range the entire city including its bridges over the Appomattox River and the rear of other Confederate batteries south and west of Petersburg. “Petersburg would surely fall if this attack succeeded.”

Burnside tapped Brigadier General Edward Ferrero’s African-American division to lead the attack. On July 29, Meade vetoed Ferrero’s division as the lead element, fearing potential fallout if the attack failed and critics claimed he had sacrificed Negro soldiers rather than risk white soldiers in a wild scheme unlikely to succeed. Burnside selected “an incompetent coward, Brigadier General James Ledlie and his division to lead.” However, Burnside was so sure of success that he packed his bags to enter Petersburg. Grant’s feint at Richmond caused the Confederate commanding general, Robert E. Lee, to move all but 18,000 men north toward Richmond. The table was set for the grand event–the explosion under the Confederate lines east of Petersburg and the Confederates were completely unaware of what was coming.

At 3:15 am on the morning of July 30, the fuses were lit. As the minutes passed, it became obvious that the fuse had burned out. Two soldiers from the 48th Pennsylvania, a lieutenant and a sergeant, volunteered to relight the fuse. These soldiers were both brave and successful, and at 4:44 am four tons of gunpowder exploded under Elliott’s Salient. 278 Confederate soldiers died in the blast. An eyewitness wrote that he “saw a huge column of dirt, dust, smoke and flame—200 feet high… I could see in the column of fire and smoke the bodies of men, arms, and legs, pieces of timber and a gun carriage.” The dimensions of the crater resulting from the blast were about 170 feet long, 60 feet wide and 30 feet deep.

Burnside’s soldiers attacked toward the hole in the Confederate lines caused by the explosion, and many went down into the crater until it was filled with men. Ultimately, about 15,000 Union troops occupied the crater and its environs, but they were disorganized and did not press forward toward Well’s Hill. Perhaps a lack of effective divisional leadership was complicit in this failure to continue the attack beyond the crater. During the attack, Ledlie drank rum in a bombproof while sending numerous orders to attack. Ferrero later joined him.

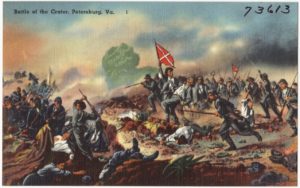

General Pierre G.T. Beauregard informed Lee of the explosion (who heard it at his headquarters at Violet Bank in Colonial Heights, north of Petersburg across the Appomattox River), and Lee ordered Brigadier General William Mahone to counterattack with three brigades. These Virginia, Georgia, and Alabama brigades attacked the “forest of glittering bayonets in the crater” while Confederate artillery poured round after round into the mass of Union infantry. Mahone’s counterattack sealed the hole in the line caused by the explosion. Colonel David A. Weisiger led Mahone’s Brigade of Virginians in the attack, which included the 12th Virginia Infantry Regiment. Of this unit’s 10 companies, six were raised within Petersburg. By 2:00 pm after over nine hours of fighting, the action was over. The casualties were approximately 4,000 Union and 1,500 Confederate soldiers. On August 1, a four-hour truce allowed both sides to retrieve the killed and wounded.

The Battle of the Crater was perhaps the most tragic event in the 9 ½-month siege, where in a one-day battle in a fairly small area almost 6,000 soldiers were killed and wounded. The Crater was “an extraordinary engineering achievement followed by a total military failure.” Grant stated this was “the saddest affair I have witnessed in this war.” The Pennsylvania Monument (near Walnut Hills Elementary School), dedicated in 1909 by President William Howard Taft, memorializes the Pennsylvania soldiers who dug the tunnel and fought in this battle.

The National Park Service’s Eastern Front Visitor Center is east of Petersburg and adjacent to Fort Lee off of Virginia Route 36. Its Eastern Front Tour is a four-mile auto route, which highlights the Siege of Petersburg from its beginning on June 15, 1864 through the Confederate attack on Union Fort Stedman on March 25, 1865. The last stop of the tour is the Crater. This is a must see!